Kyruus Health Blog

View the latest on care access and industry transformation

Sign up to get the latest insights right to your inbox.

From Compliance to Consumerism and Engaged Members

April 25, 2024In a recent session at t

Read MoreAssessing the Impact: 2024 Provider Directory Requirements

April 16, 2024As part of our commitment to our clients, we regularly monitor proposed and passed regulatory and

Read MoreMoving Beyond EHR Based Engagement to Deploying Consumer-Centric Strategies that Empower Communities

April 2, 2024As usual HIMSS was a whi

Read MoreCelebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Community – Sydney Edwards

February 29, 2024Introducing the latest chapter in our “Celebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health

Read MoreCelebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Community – Pam Clark

February 22, 2024Embracing the spirit of unity, strength, and shared humanity, we present the fourth installment o

Read MoreBeyond the Schedule: ViVE2024’s Can’t Miss Sessions and Receptions

February 21, 2024ViVE2024 is just around the corner, and we’re gearing up for a week of insightful conversat

Read MoreCelebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Community – Ron Otoo

February 16, 2024Welcome to the third installment of our “Celebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Heal

Read MoreCelebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Community – Tina Brown-Stevenson

February 8, 2024Introducing our second blog in the “Celebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Commun

Read MoreCelebrating Diversity: Voices from our Kyruus Health Community – Denean Greene Rivers

February 1, 2024In honoring Black History Month, Kyruus Health is proud to amplify the voices within our vibrant

Read MoreEmbracing Change: A Glimpse into Kyruus Health’s Transformative Rebrand

January 8, 2024The air has been buzzing with excitement as our team officially unveils Kyruus Health. Keep reading to explore the driv

Read More3 Steps Healthcare Organizations Can Take to Provide Consumers with a Seamless Digital Experience

October 26, 2023Today’s healthcare consumers have a decided preference for digital self-service when it comes to searching for, select

Read MoreOnline Scheduling: It Doesn’t Only Benefit Patients

October 25, 2023No matter how good you are at multitasking, there are still only 24 hours in a day and seven days

Read MoreThought Leaders: Simplicity, Flexibility to Shape the Future of Patient Access

October 23, 2023While the future of patient access is digitally-enabled, when it comes to helping consumers find and schedule care, simp

Read MoreTips to Bring Your IDN’s Digital Experience (Actually) Under One Roof

October 23, 2023The healthcare industry is evolving at an unprecedented rate to keep pace with changing customer needs, government manda

Read MoreDigital Self-Service: A Must Have for Consumers

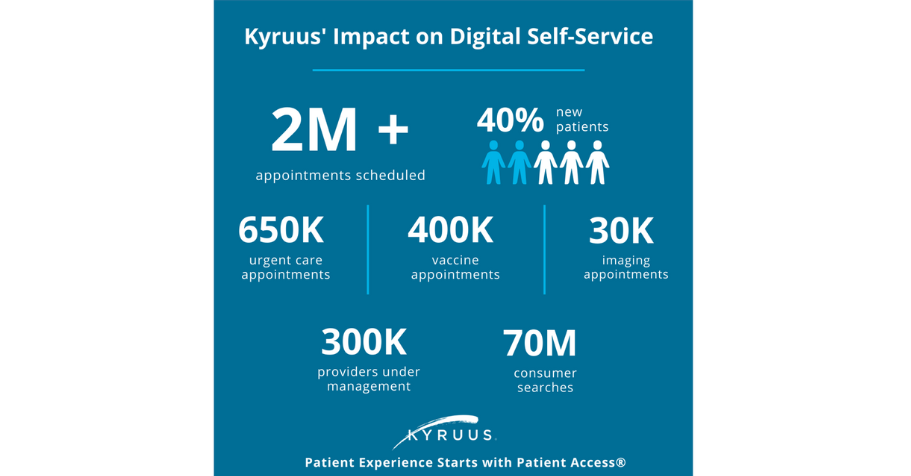

October 23, 2023Online scheduling and access to digital self-service continue to be top priorities for consumers. In fact, 40% of consu

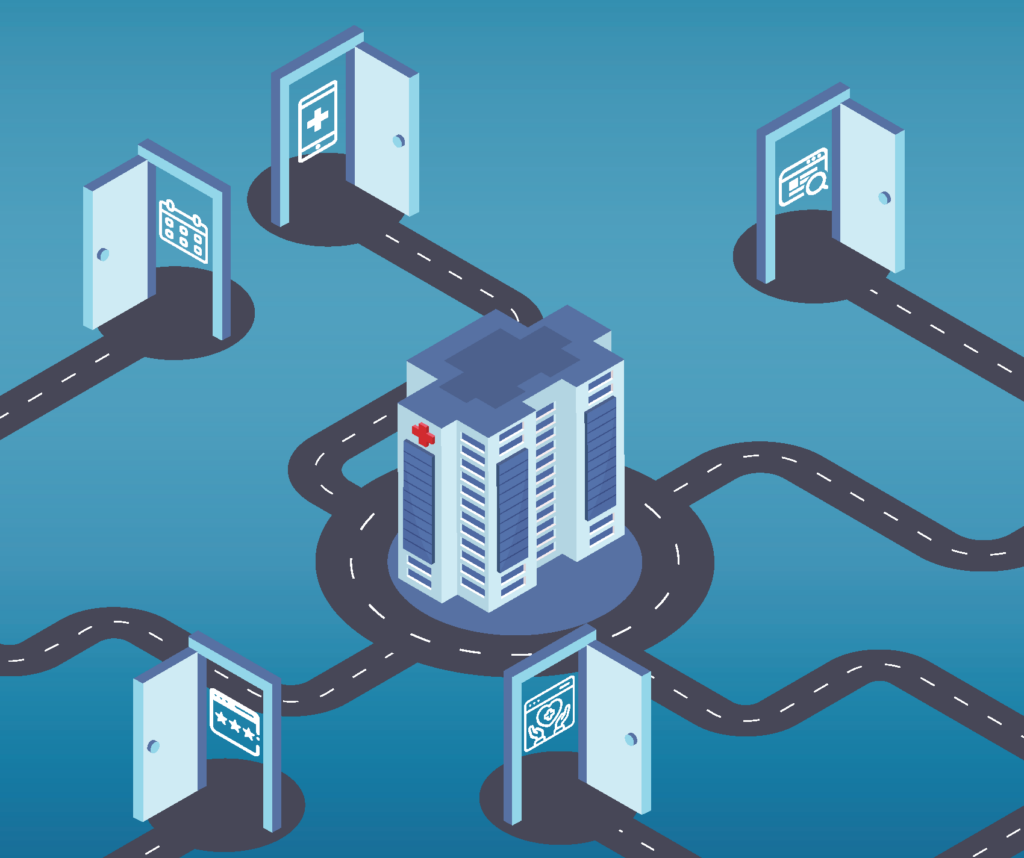

Read More3 Top Strategies for Opening All the Digital Doors for Healthcare Consumers

October 23, 2023The “digital front door” has been a critical element of patient access strategies across healthcare organizations fo

Read MoreDemonstrating the Value of Patient Access in Challenging Times

October 23, 2023It’s no secret: most healthcare organizations today are facing significant financial challenges—and there isn’t a

Read MoreBecker’s Payer Roundtable Recap: Are Payviders Supervillains or Superheroes?

October 23, 2023Of all the terms used at Becker’s Payer Issues Roundtable in early November—including Integrated Delivery Network (I

Read MoreVoices from the Frontlines: Key 2022 Consumer and Provider Research Findings

October 23, 2023Keeping a steady pulse on both consumer and provider perspectives is vital to ensuring Kyruus’ solutions meet the need

Read MoreHelping Consumers Find a “Provider Like Me” and Why It Matters

October 23, 2023With nearly 60% of consumers using the internet to find a new provider, it’s critical for healthcare organizations

Read MoreThree Ways Medical Groups Can Leverage Digital Self-Service to Drive Growth

October 23, 2023That medical groups and health systems share a commitment to delivering convenient, high-quality care in their respectiv

Read MoreThe Results Are In: Patients Definitely Prefer Digital Self-Service

October 19, 2023Sometimes it’s nice to have things done for you. Maybe someone made you a delicious dinner or fixed a flat tire on you

Read MoreConsumer Choice and Expectations: Highlighting the 2023 Care Access Benchmark Report

October 11, 2023These days when consumers are considering their care options, they have more than just a few providers to choose from. T

Read MoreNew Research Reveals the Top 3 Things Members Want from Their Health Plans

October 10, 2023Beginning in July 2023, Wakefield Research surveyed 1,000 individuals across the country on behalf of Kyruus to gain an

Read MoreDon’t Snooze on the Benefits of Digital Health for Your Sleep Medicine Practice

October 4, 2023Getting enough sleep might seem like a luxury, but doing so is important for your overall health. Not only has insuffici

Read MoreDon’t Snooze on the Benefits of Digital Health for Your Sleep Medicine Practice

October 4, 2023Getting enough sleep might seem like a luxury, but doing so is important for your overall health.

Read MoreDoes Your Pain Medicine Practice Know the Value of Digital Health?

September 27, 2023If you’re human, physical pain is part of your life, at least from time to time. For more than 50 million adults in th

Read MoreHow to Apply Digital Health to Make Behavioral Health Care More Accessible for Your Patients

September 20, 2023It has been a little more than four months since the United States government announced that the COVID-19 Public Health

Read MoreDigital Health: Added Convenience for Urgent Care Centers

September 13, 2023You’re at your son’s Friday night football game when he collides with a player from the other team. He’s not serio

Read MoreHow Digital Health Tools Help FQHCs Increase Access to Care

September 6, 2023Approximately 60 million United States residents live in rural areas. That’s 15% of the country’s total population.�

Read MoreDigital Self-Service Tools for Orthopedic Practices: 3 Tips for Expanding Convenient Access to Care

August 30, 2023EmergeOrtho is North Carolina’s largest physician-owned orthopedic practice with a team of nearly 270 highly-trained o

Read MoreOnline Scheduling: It’s Not Just for Doctor’s Appointments Anymore

July 26, 2023There are more than 1,077,000 professionally-active doctors providing care across the United States. Of those, a little

Read MoreA Study in Success: How collaboration leads to significant impact for one plan partner

July 20, 2023HealthSparq and a health plan client recently spoke with Health Plan Alliance (HPA) members about breaking down access b

Read More3 Key Considerations for a Successful Provider Data Management Strategy

July 13, 2023We recently had the privilege of hosting Amber Welch, VP of Digital Marketing, Platforms & Planning from Ochsner He

Read MoreThe Importance of Meeting Patient Preferences

July 12, 2023Not all patients prefer the same type of doctor. Some like a physician who has been in practice for at least a couple of

Read MoreThe Cost of Delayed Care — and How Digital Health Can Help

June 28, 2023After three seemingly unending years, the COVID-19 pandemic is officially over — according to the United States govern

Read MoreThe Importance of Negating Patient No-Shows

June 21, 2023Whether you write everything down in a daily planner or simply keep a mental list, chances are you’re going to forget

Read MoreThe 3 Most Popular Digital Health Tools for Contactless Care

June 14, 2023Contactless care. It might have sounded futuristic a decade or so ago, but these days, it’s an important component of

Read MorePatient Experience Vs. Patient Satisfaction: What’s the Difference?

June 7, 2023Patient satisfaction. Patient experience. Patient engagement. Patient-centered care. Patient retention. There are so m

Read MoreGuide Patients to the Right Care With Your Find Care Experience

May 25, 2023Consumers want convenience, flexibility, and seamless digital access that includes self-service tools to help them confi

Read MoreHow Much Does a Negative Patient Experience Cost You?

May 24, 2023A patient’s experience encompasses more than just a direct interaction with their doctor. It spans their entire care

Read MoreClosing CAHPS Gaps

May 23, 2023Prioritizing provider data accuracy to avoid negative impact In today’s healthcare landscape, patients not only wa

Read MoreUtilizing Digital Health to Help Combat the Opioid Epidemic

May 17, 2023One hundred thirty. That’s — on average — how many Americans die every day from an opioid overdose. The federal

Read MoreNurses: Overcoming Obstacles to Provide Quality Patient Care

May 8, 2023Unless you’re a robot, made of Teflon, or somehow immune to injury or illness, chances are you’ve been treated by a

Read MoreThe 85-million-person Challenge: Medicaid and Your Members

May 8, 2023Getting care is hard enough – connecting members with the right provider shouldn’t be part of the challenge. With ov

Read More4 Ways to Enhance the Productivity of Your Medical Group’s Front Office

May 3, 2023You go to a new restaurant for dinner. The food is tasty, but the service is horrible. Chances are you’re probably not

Read MorePreparing for the future of Price Transparency: Scaling for member experience

May 2, 2023As the final deadline for the Transparency in Coverage mandate rapidly approaches on 1/1/24, many payers continue to fac

Read MoreDigital Health: Promoting a Positive Patient Experience

April 26, 2023It’s been more than 15 years since the Triple Aim was developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). One

Read MoreImproving the Member Experience through Payer-Provider Collaboration: Reflecting on the Becker’s Payer Issues Roundtable

April 20, 2023Dr. Reetika Kumar from Independence Blue Cross (IBX) and Jeff Stuart from CHRISTUS Health sat down with Kyruus’ Presid

Read MoreThe Advantages of Patient Self-Scheduling

April 19, 2023Convenience. It’s something most Americans expect now, whether having dinner or groceries delivered simply by using a

Read MoreInvesting in Centralized Provider Data Management to Power Digital Health Initiatives

April 13, 2023As organizations are looking to make strategic technology investments that have significant impact across their organiza

Read MoreWhat is Physician Burnout Costing You?

April 12, 2023If you experience symptoms of a mental health condition, you’re not alone – by any means. More than one in five adul

Read More5 Ways to Improve Patient Collections

April 5, 2023New isn’t always better. Some products made these days with more advanced technology might seem to be improved but lac

Read MoreHealthcare Consumerism in 2023

March 15, 2023When’s the last time you went shopping at the local mall or waited in line to purchase concert tickets? If you’re

Read MoreThe Primary Care Physician Shortage by State

March 8, 2023The United States Census estimates that the number of Americans over age 65 will grow by almost 10 percent by the year 2

Read MoreFrom contract to partnership: executive perspectives on payer-provider collaboration

March 7, 2023At HLTH22 last fall, the CEO of Blue Shield of California, Paul Markovich, shared his thoughts on partnerships between p

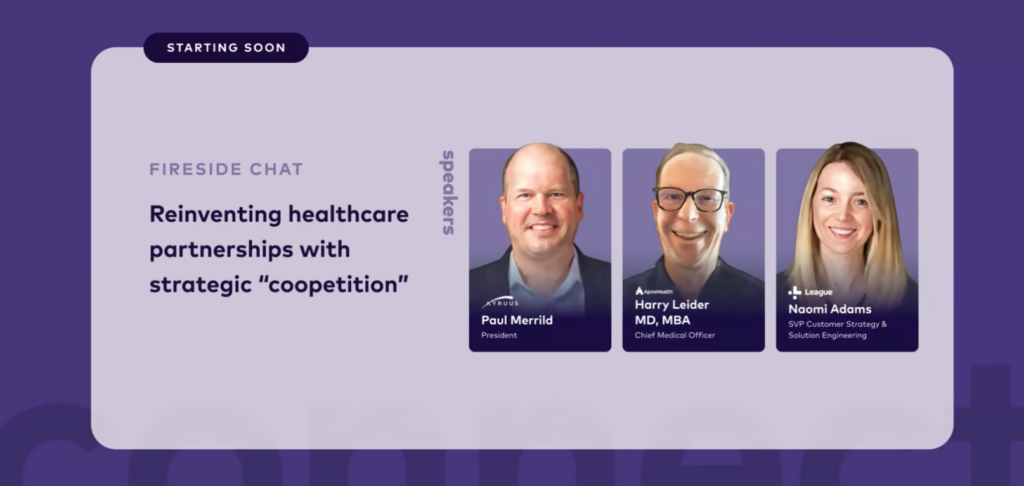

Read MoreFill in the Gaps: Partnering Strategies in Healthcare

March 1, 2023At the recent League Connect conference, Paul Merrild, president of Kyruus and HealthSparq, and Harry Leider, chief mark

Read More6 Ways Your Practice Can Increase Patient Satisfaction

March 1, 2023The customer is always right. This phrase, which is regularly bandied about, allegedly originated from Swiss hotelier C�

Read MorePhysician Depression: Rates and Resources

February 22, 2023It’s been nearly 50 years since psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, who often volunteered at a free clinic in New York

Read MorePutting Patient Feedback to Work for Your Practice

February 16, 2023There’s always room for improvement. You’ve undoubtedly heard that phrase multiple times. No one knows for sure who

Read More4 Ways to Increase Your Patients’ Utilization of Digital Health Tools

February 8, 2023Sporting goods stores and online businesses are full of home exercise products touting unparalleled health benefits. Tre

Read MoreHow Burnout Is Affecting Allied Healthcare Professionals — and What Can Be Done About It

February 1, 2023Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a plethora of clinicians have reported symptoms of exhaustion, depression, sle

Read MorePatients Are Prioritizing Digital Access — What Should Health Plans Know to Keep Them Engaged

January 25, 2023People have continued to evolve as they search for and select care—adopting sophisticated shopping behaviors similar t

Read More“It’s Not About a Killer App”: CIO Perspectives on Digital Transformation

January 23, 2023Guest contributor Kate Gamble, Managing Editor & Director of Social Media at healthsystemCIO, summarizes key findi

Read More20 Tips for Healthcare Providers to Keep Their Mobile Devices Secure

January 18, 2023The average adult in the United States spends 3 hours and 43 minutes on their mobile devices. That tallies up to 50 days

Read MoreHelping Consumers Find a “Provider Like Me” and Why It Matters

January 17, 2023Selecting a provider is a personal and nuanced decision for consumers—one that launches a journey of discovery that ty

Read MoreNew Research: Health Plan Execs Talk Transparency

January 12, 2023For most people, January means a new health plan benefit year. But, this year is different. Now all health plan members

Read MoreThree Global Health Issues to Watch in 2023

January 11, 2023If you’ve ever had the chance to travel overseas, you’ve undoubtedly experienced cultures and traditions that differ

Read MoreThe Biggest Barriers to Accessing Healthcare — and 10 Things You Can Do to Address Them

January 4, 2023Unless you live in the south or work remotely from a tropical island, the weather right now is probably very cold. Some

Read MoreReducing Call Center Volume: Tips and Strategies to Maximize Online Self-service Provider Directories

December 19, 2022For most health plans, the number one reason members call into the call center is related to finding a provider – and

Read MoreThe Top Three Challenges of Technology in Healthcare

December 14, 2022Wireless headphones, robot vacuums and e-readers are three of the most-requested gifts this Christmas. Unlike a few deca

Read MoreHow Does Cost Affect Access to Care for Your Patients?

December 7, 2022There was a time when you had to use a paper map to plan your road trip. No simply plugging in your destination and gett

Read MoreThe 5 Biggest Rural Healthcare Challenges in the U.S.

November 30, 2022What do Telluride, Colorado, Sedona, Arizona and Kennebunkport, Maine all have in common? They’ve all been included in

Read MoreThe Valuable Impact of a Patient and Family Advisory Council

November 22, 2022What is a Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) and why would you have one as part of a healthcare software company

Read MoreBecker’s Payer Roundtable Recap: Are Payviders Supervillains or Superheroes?

November 17, 2022Of all the terms used at last week’s Becker’s Payer Issues Roundtable – including Integrated Delivery Network (IDN

Read MoreHow Consumers Prefer to Find, Select and Access Healthcare

November 16, 2022Facebook, YouTube and Amazon might be the most-searched terms online, but it didn’t start out that way. Actually, the

Read MoreBuilding a Provider Search Experience Members Can Trust

November 15, 2022It may sound like a no-brainer, but conflicting information about healthcare providers across platforms (think health pl

Read More8 Reasons Healthcare Providers Should Prioritize Patient Self-Service

November 9, 2022Pumping your own gas might seem like a regular occurrence, but that wasn’t always the case. Before Colorado convenienc

Read MoreHealthcare Costs Remain A Major Concern For Health Plan Members

November 9, 2022As 2022 rapidly draws to a close, fresh consumer insights shed light on how consumers are feeling about healthcare costs

Read More5 Myths About Older Adults and Technology We Should All Stop Believing

November 2, 2022Most of us as children want to grow up quickly. We envision being an adult and enjoying all the benefits that go with it

Read MoreAre You Ready To Market Price Transparency?

November 2, 2022Product, data, and engineering teams at health plans have been hard at work building solutions to meet the January 1, 20

Read MoreHow to Improve the Customer Experience in Healthcare

October 26, 2022We’re all customers. Whether you’ve purchased a new car, paid someone to install a pool in your yard — maybe a lar

Read MoreHow to Build The Provider Directory Tool That Keeps Members Coming Back

October 25, 2022As one of the most utilized resources on a health insurer’s website, a provider directory should have rich data an

Read MoreFive Ways to Tackle Lengthy Patient Wait Times

October 19, 2022Waiting. It evokes various types of feelings, from hope all the way to uncertainty. Biding time for a scheduled vacation

Read MorePatient-Centered Care: Why is it Important?

October 13, 2022Patient engagement. Patient satisfaction. Patient intake. Patient flow. Patient volume. Patent access. What’s at the

Read MoreWhat Is Health Literacy and Why Is It So Important?

October 13, 2022Healthcare providers are facing new challenges balancing quality of care and optimal use of dwindling resources. The cos

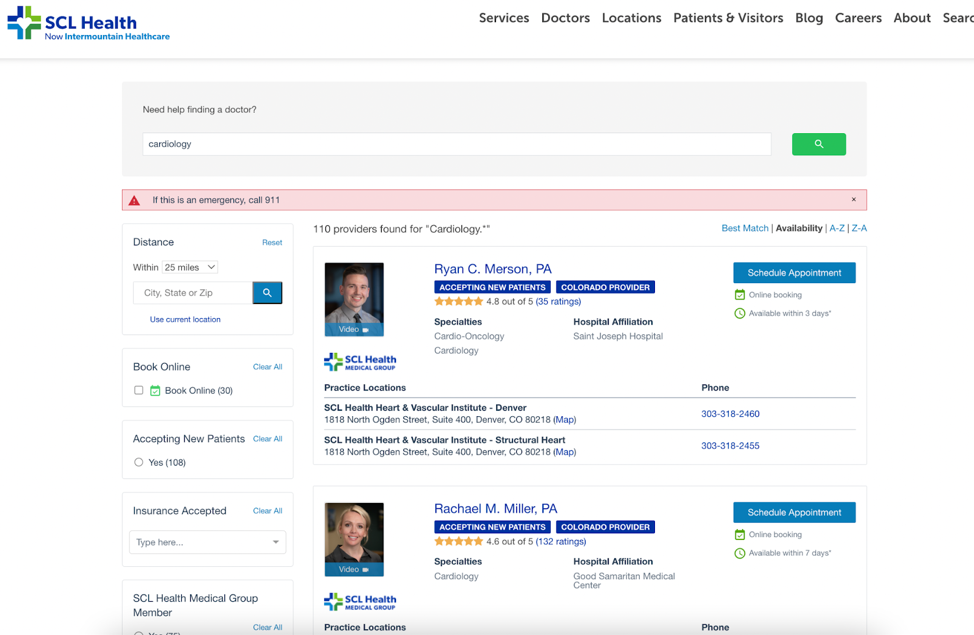

Read MoreLegacy SCL Health (Now Intermountain Healthcare) Reimagines Digital Patient Access

October 12, 2022As expectations for digital self-service continue to grow, healthcare organizations should regularly assess their digita

Read MoreLooking to What’s Next in CX for Health Plans: Highlights from #AHIPDigital

October 7, 2022We recently attended the annual AHIP Consumer Experience and Digital Health Forum in Nashville. At this year’s event,

Read More10 Recommendations for Helping Patients With Low Health Literacy

October 5, 2022The road to becoming a physician is paved with years of education and training — not to mention a lack of sleep and a

Read MoreHow Much Does Healthcare Really Cost?

September 28, 2022When people make purchases, one of the first questions is “how much?” And when it comes to big purchases, like a car

Read MoreWhy Interoperability Should Be a Priority for Your Medical Group

September 28, 2022If you’ve ever heard the Johnny Cash song “One Piece at a Time,” you know it’s about two assembly line coworkers

Read More10 Expert Tips: How to Become an Effective Healthcare Leader

September 21, 2022In a 60 Minutes interview with host Mike Wallace nearly 50 years ago, former president Ronald Reagan expressed his thoug

Read MoreWhat to Watch Out For with Using MRFs for Self-Service Tool Compliance

September 8, 2022Last month was a major milestone for the healthcare industry. From 2019 when the federal Transparency in Coverage (TiC)

Read MoreGuide and engage members with price transparency

September 1, 2022Many health plan teams have spent the last year heads down, working diligently to meet Transparency in Coverage mandates

Read More10 Advantages to Using Digital Patient Check-In Platforms

August 31, 2022Paper is suitable for a lot of things. It’s used for money, greeting cards, media publications and more. It’s so pop

Read MoreHow Digital Patient Intake, Registration Boost Patient Experience

August 23, 2022It’s easy for a patient to become overwhelmed visiting the clinic or hospital. Even the patient intake process is rife

Read MoreIt’s All About Me: Providers Say Digital Profiles Are Their Chance to Shine

August 9, 2022Online profiles are digital calling cards that must be accurate, comprehensive, and present across channels, according t

Read More5 Apps Your Healthcare Practice Needs Now

August 3, 2022There are more than 350,000 healthcare apps available, from those used to help patients track their calorie intake to

Read MoreBuilding Providers’ Digital Presence: Here, There, and Everywhere

July 27, 2022Nearly 80% of providers say a high-quality digital presence on their healthcare organization’s find-a-provider website

Read MoreThree KPIs That Help Providers Measure Their Progress in Value-Based Care

July 27, 2022Getting value out of a purchase or investment can certainly be satisfying, especially at a time in the United States w

Read MoreGetting Started with Online Scheduling: 5 Key Steps for a Successful Launch

March 2, 2023Today’s consumer is accustomed to doing everything online—and its no shock that this preference carries over int

Read MoreShore Physicians Group: Achieving a Mission to Keep Patients Well-Connected

January 25, 2023When Shore Physicians Group was founded in southern New Jersey a little more than ten years ago, only about half of all

Read MoreInsights from Banner Health: How to Transform Your Digital Front Door

July 28, 2020There is little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly reshaped the delivery of care in the United States. We h

Read MoreRewarding Healthcare Choices: Matt’s Story

January 28, 2019It’s always such a nice surprise when we hear directly from people who are benefitting from our solutions. Just recent

Read MoreGet in touch

Learn more about how Kyruus Health

can transform your appproach to connecting

people to the right care.